… helping you get a bit smarter

Lithium batteries back up power stations

Batteries are critical to the development of portable (electrical) devices. And lithium-ion batteries have been up there in driving the portability revolution. Rechargeable lithium-ion batteries hold more charge in a lighter package (as lithium is the lightest metal – hydrogen is not a metal) and have dramatically improved the performance of phones to small electric aircraft. But they do have one drawback – they charge and discharge too rapidly (and the resultant heat can damage the battery or cause a fire). So they need constant monitoring and control by a built-in electronic circuit to avoid this problem.

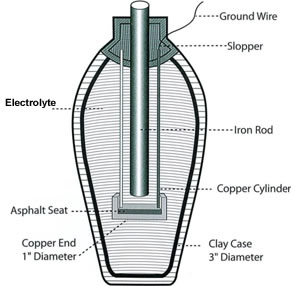

Construction and operation

The basic construction elements of lithium-ion batteries are individual cells. Each cell comprises two electrodes separated by electrolyte (a gel). When the battery is being charged, the lithium ions migrate from the positive electrode (lithium material) to the negative electrode (carbon) through the gel. When the battery is providing the power, the process is reversed.

Generally, the positive electrodes are made from lithium iron phosphate but an innovative company (Corvus in Vancouver – Canada) use lithium nickel manganese cobalt, because it can provide a greater power density (by more than 20% on conventional lithium iron phosphate). Each cell is placed into 6.2kWh modules, which can be placed together to store an unbelievable MWh. Using some nifty electronics, these 6.2kWh modules can be charged from zero to full in as little as 30 minutes, and able to be discharged in 6 minutes. Corvus claim 3000 charging cycles based on a 100% depth of discharge (till completely flat). Theoretically, if the depth of discharge is only 80%, 300,000 cycles are achievable. Although, being cynical about claims like this, I would doubt it would be of this order.

Dollars and cents and applications

These modules are still much more expensive compared to the other more usual batteries ($9300 against $7500 for standard lithium iron phosphate). The suggestion is to use these mega batteries in applications such as diesel engines which idle for long periods of time where these batteries could provide the necessary power. Thus resulting a ferocious reduction in carbon dioxide (and burnt fuel) emissions. Or alternatively replace diesel engines with electric motors powered by batteries due to the increased efficiencies. And also as an application in electric cars – a recent one with a lithium battery travelled 600km from Munich to Berlin non-stop at an average speed of 90km/h.

Renewable energy sources such as from wind and solar are highly variable. Battery technologies that decrease the cost per watt of renewable energy would be a boon.

Intriguingly, China has ordered a 2.2 MWh lithium battery from Canada for back up to a coal-fired power station.

Finally, lithium is not a rare element. It is produced in countries such as Chile, Australia and China and recyclable, so in seemingly inexhaustible supplies.

| Print article | This entry was posted by admin on November 4, 2010 at 8:15 am, and is filed under Devices. Follow any responses to this post through RSS 2.0. You can leave a response or trackback from your own site. |